‘Shadow pandemic’ of femicide looms, experts warn as Canada prepares to reopen

After more than a year of quarantines, lockdowns and separations due to COVID-19, Canada is slowly reopening. But experts say another pandemic, of femicide and domestic violence, has been quietly raging across the country.

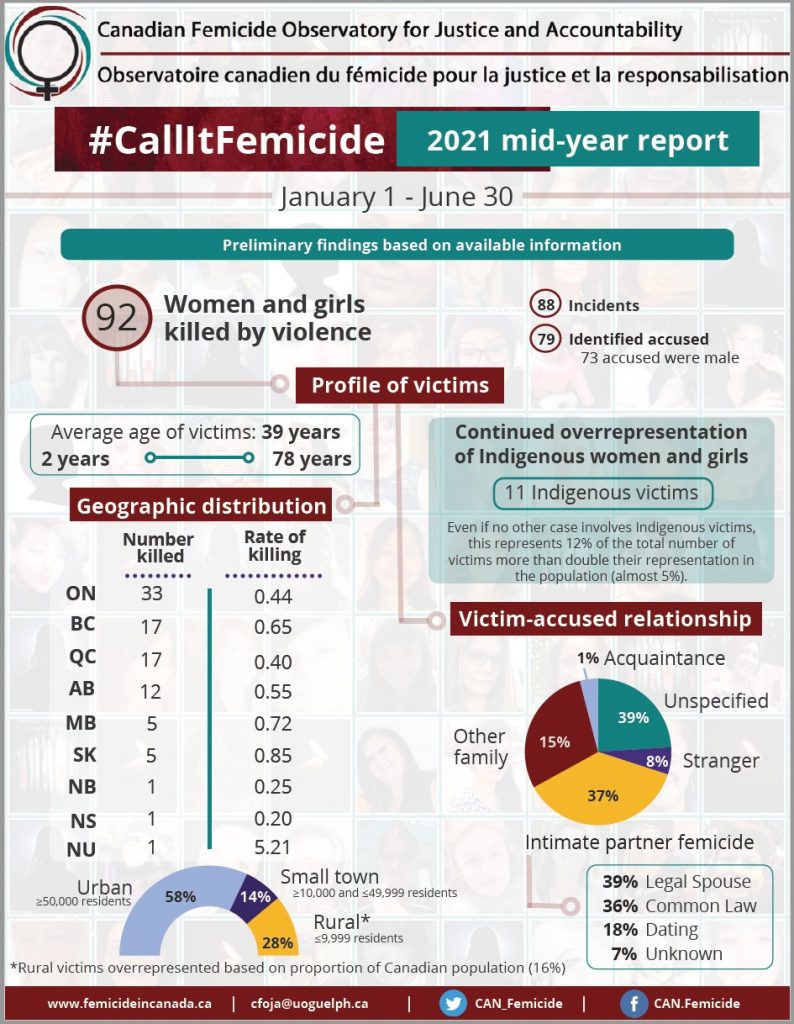

The proof is in the reports. Preliminary findings from the Canadian Femicide Observatory for Justice and Accountability’s (CFOJA) mid-year report found 92 women and girls were killed, mostly by men, between January and June of this year.

Femicide is the killing of a girl or woman because of their gender. Men were identified as the accused in 79 out of 92 killings in the first half of 2021.

Indigenous women were over-represented in this year’s report, making up 12 per cent of femicide victims, despite comprising just 5 per cent of Canada’s overall population.

Experts say the data is unsurprising.

“We, as in violence against women organizations, advocates and survivors, have been naming that there is a shadow pandemic happening and that is gender based violence,” says Farrah Khan, a gender justice advocate and manager of Ryerson University’s Office of Sexual Violence Support and Education.

Numbers have been steadily rising since the COVID pandemic began. CFOJA, which tracks femicides across the country, said 160 women and girls were victims of femicide last year, an uptick from the 118 who were killed in 2019.

Khan said the health crisis that has led to repeated lockdowns across the country has “set women up” for unhealthy relationships that could result in their deaths. Women, who were disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, accounted for more than 35 per cent of job losses across the country and make up a majority of Canada’s minimum wage workers.

She says this could have prompted many women to move in with potentially abusive partners to save on costs that left them trapped and unable to leave when things began to escalate in an unsafe way. Things like child-care problems and food insecurity, also rampant during the pandemic, are also reasons women end up trapped with their abusers.

“The lockdown has increased the abusers’ access to them, has increased their ability to control their mobility, increased their ability to set strict rules about who they interact with,” she said of women during the pandemic, including those with abusive family members.

“I worry about the people also that are living through it right now that are not reaching out to services, are not feeling safe to do so because someone is monitoring their phone, somebody is monitoring their computer.”

Of the 160 women killed according to the report, researchers said 128 women and girls were killed by men. A majority of them were killed in the Northwest Territories and Nunavut accounting for 13.68 per cent and 5.21 per cent respectively.

Victims of abuse could see more challenges in rural and remote areas, Khan says, because of isolation and the lack of mobility sometimes present in those communities.

“Already mobility is challenged. Already there’s no computer in the house that doesn’t have spyware on it,” Khan said, adding that “what’s needed in Toronto is different than what’s going to be needed in rural and remote areas.”

Numbers are also stacking up in more densely populated provinces.

In Ontario alone, femicide has increased by more than 84 per cent in the first half of 2021, according to the latest report from the Ontario Association of Interval and Transition Houses (OAITH).

From December 2019 through June 2020, the report found 19 confirmed femicides throughout the province. The next year, they reported 35.

Younger women between the ages of 18 and 35 accounted for a majority of this year’s femicides at 30 per cent, while younger men between 18 and 35 years accounted for 50 per cent of all perpetrators this year. Researchers found intimate partner cases made up 80 per cent of femicide cases in 2021.

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, Ham said OAITH began noticing more femicides in Ontario when the province reopened, likely as a result of women trying to leave their abusers.

“When survivors leave or make a plan to leave, for some of them that can be the most dangerous time,” she said.